RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT Stress, trauma, and the brain in chronic pain

New research reveals that stress and trauma reshape key brain regions differently in people with chronic pain.

Stress and pain don’t affect everyone equally

Researchers at the NeuroRecovery Research Hub, School of Psychology at UNSW Sydney, and the Centre for Pain IMPACT at NeuRA are uncovering how experiencing very stressful or traumatic events changes the brains of people with chronic pain.

Stress can weigh heavily on the body and mind, but a recent study from Yann Quidé and colleagues shows that for people living with chronic pain, the impact of stress and past trauma goes even deeper.

While someone without chronic pain may recover more easily after stressful experiences, people with ongoing pain seem to show stronger and longer-lasting changes in brain regions important for emotion regulation, empathy, and how pain is experienced.

The brain responds differently when pain is chronic

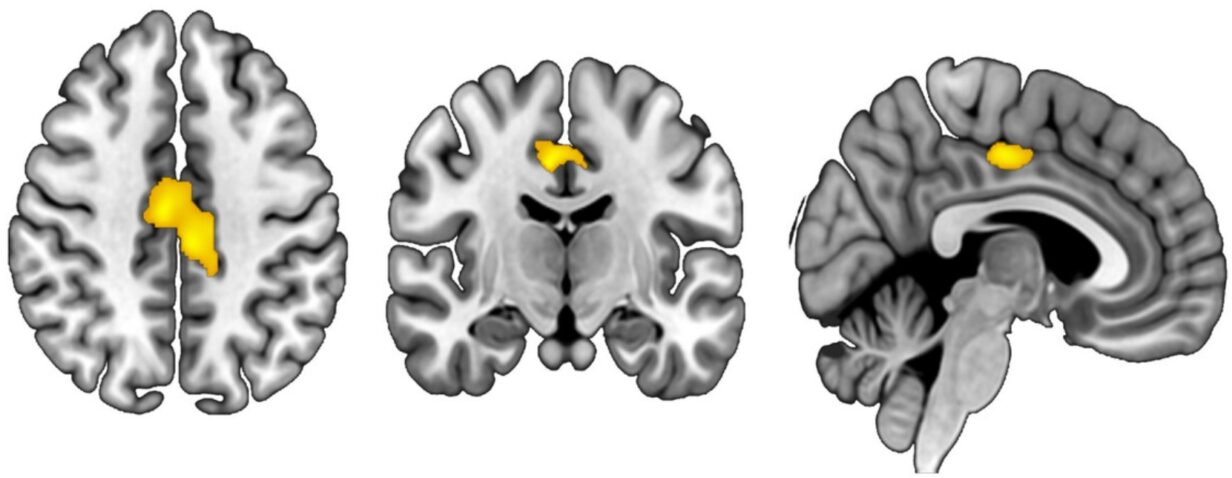

One key region, the mid-cingulate cortex, is central to how we process both our own pain and the suffering of others. In people with chronic pain, stress and trauma are linked to a reduction in the size of this area, suggesting the brain is physically reorganizing itself under the combined strain of pain and stress.

For those without chronic pain, stress does not appear to drive these changes to the same extent. This may help explain why living with chronic pain often feels more overwhelming and isolating.

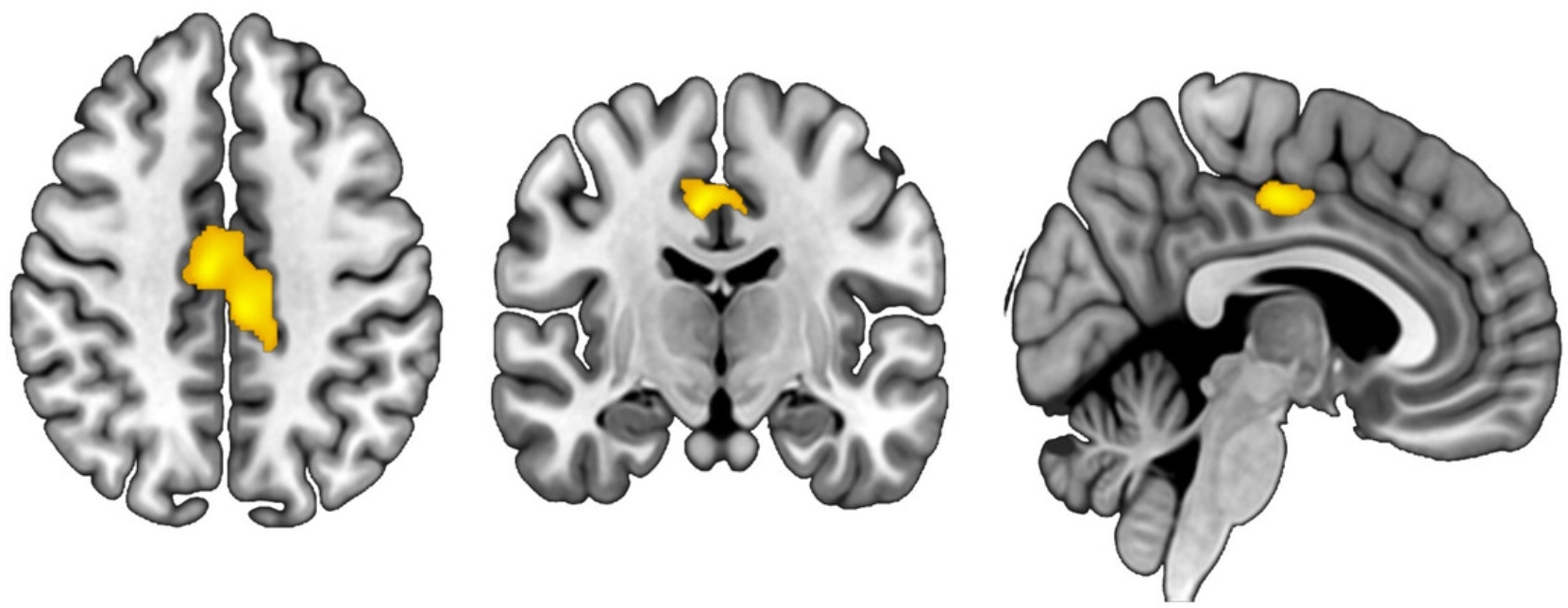

The study also highlights another important region: the posterior insula, a region that helps process pain signals and how we interpret them.

In people with chronic pain, increased stress was associated with a smaller posterior insula, again pointing to brain reorganization under the combined pressures of pain and stress; this effect was less apparent in those not experiencing chronic pain.

A reinforcing cycle between stress and pain

These findings highlight how stress and pain can create a cycle that is hard to escape. Stress makes brain regions such as the mid-cingulate cortex and posterior insula more sensitive to pain, and greater pain then leads to more stress.

For people without chronic pain, the brain may be able to cope better with stress, breaking the cycle before it strengthens. But for those already living with long-term pain, stress can lock the brain into patterns that sustain pain, potentially making pain harder to manage.

New perspectives for managing pain

If stress and trauma have a stronger impact on the brains of people with chronic pain, then treatments that focus on reducing stress (for example, mindfulness) and restoring emotion regulation (for example, the Pain and Emotion Therapy developed by our group) may be especially effective.

This research indicates that managing chronic pain isn’t just about easing physical symptoms, but also about protecting and supporting the brain.

Read the full research paper here: Yann Quidé, Negin Hesam-Shariati, Nell Norman-Nott, James H. McAuley, Sylvia M. Gustin. Stress-Related Brain Alterations in Chronic Pain, European Journal of Pain,29(6), e70034; DOI: 10.1002/ejp.70034

Recent Comments